The ad blocking paradox

As web ads get more and more closely targeted to the user, more and more users are choosing ad blockers and tracking protection tools such as Privacy Badger, Disconnect and Ghostery. According to a survey by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, most US users “are not okay with online targeted advertising.”

Targeted ad proponents tell us that ads are getting more personalized and relevant, so why isn’t blocking going down instead? Why aren’t users saying, There’s a magic machine in a data center that will only show me ads for stuff I really want to buy? Better turn off the ad blocker!

In another survey, 66% of adult Americans said they do not want marketers to tailor advertisements to their interests

, and when the researchers explained how ad targeting works, the percentage went up.

The Apple Safari product page treats the browser’s tracking resistance as a benefit.

The web pages you visit often leave cookies from third-party websites. These cookies can be used to track where you go on the web, target you with ads, or create a profile of your online activities. Safari was the first browser to block these cookies by default. And by default it also prevents third-party websites from leaving data in your cache, local storage, or databases."

Why does the biggest, best-run company in information technology, the company that inspires more marketing people than any other, just assume that people don’t want web sites to “target you with ads?” Apple could easily implement more tracking than other browsers. Why don’t they? Why doesn’t Apple’s browser “help you connect and share with your favorite brands”?

The reasons are complicated, but they’re connected to why ad blocking is finally taking off.

For a long time, web ad blocking was available but rare. Early ad-blocking products such as “Internet Junkbuster”, “WebWasher”, and “AdSubtract” were all just as easy and effective as the ad blockers of today. At dial-up speeds, they made browsing noticeably faster. But from 1996 to 2009, few users chose to block ads. A 2002 survey by Forrester Research found that only 1% of users were using an ad blocker.

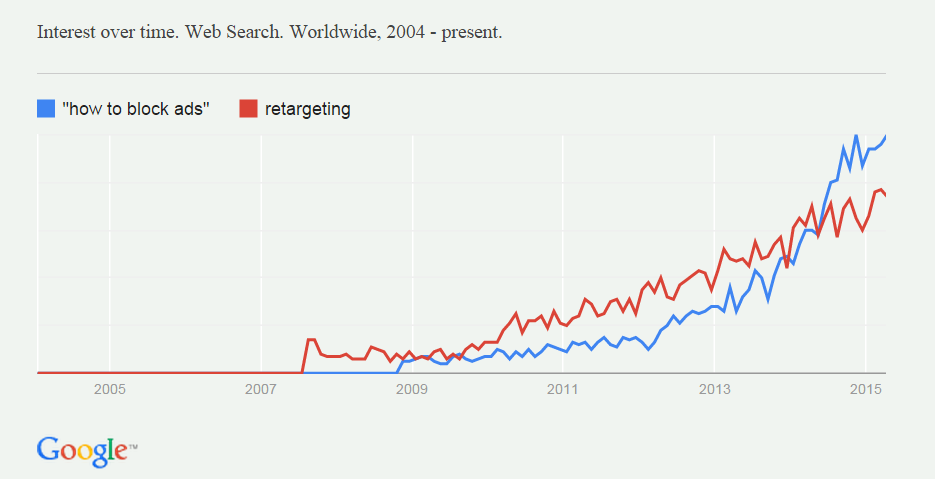

Starting in 2009 or 2010, though, something changed. Ad blocking has gone mainstream. One startup, ClarityRay, reported in 2012 that 9.26 percent of all ad impressions on 100 popular sites were being blocked. Ad blocking grew along with retargeting, which caused users to see ads “following them around” from one site to another.

Retargeting makes it obvious to a user that this ad is for you, not just attached to the content. The Wall Street Journal’s What They Know series started to increase awareness of ad targeting, and other news sites reported on it as well. Jason Kint writes, “Online advertising is trusted less than any other form of advertising. When we see examples like the St. Louis Post Dispatch’s approach to online advertising, we shouldn’t be wondering why consumers are flocking to ad blockers in droves.”

Web ads are consistently less valuable to advertisers than ads in older media. The more targetable that an ad medium is, the less it’s worth, as seen in Mary Meeker’s Internet Trends 2012. What is going on with “print”? It took up seven percent of people’s media time, but 25% of ad budgets. The trend continues in Internet Trends 2013. Print has 6% of the time and 23% of the money. For 2014, it’s 5% of the time and 19% of the money. In 2015, print loses another 1% of time and money, but still pulls in 3/4 of the web’s revenue in 1/6th the time.

Compared to print, the value of the web as an advertising medium is staying unnaturally low relative to time spent. By 2017, mobile ads are hot, but still weak in money per minute, while web ads somehow stay pretty much in the same commodity spot, despite generations of technical innovations.

We’re not just looking at some kind of inertia effect here, where media buyers just keep wasting their money on print because that’s what they have always done. It’s the opposite—print is a relative bargain. 2016 research from Nielsen Catalina Solutions shows return on ad spend of $3.94 in magazines, compared to $2.63 for online display ads, $2.45 in mobile, and only $1.53 in digital video. Somehow the lowest-tech, least user-targetable ad medium is creating the most value for advertisers.

What does print have that online doesn’t?

Print advertising has the sweet spot of awesome: it’s easy to place an ad based on content, but hard to track individuals.

Hard to track individuals? How is that a good thing? And, without going back to print, what can the web do to become as valuable to advertisers as print has been?

ADVERTISEMENT

We have a few steps to work through here. So let’s start with some Nobel-Prize-winning economics research.

How can markets survive information asymmetry?

Here it is: Akerlof, George A. (1970). “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism”. (There’s a summary on Wikipedia.)

Let’s say you have a car that runs fine for now, but that you know won’t last long because of the time with the attempted oil change and the drain plug you found in a pool of oil in the driveway and you cleaned up all the oil with kitty litter but…anyway, you know bad things about the car that a buyer couldn’t. You’re looking to sell. Meanwhile, a seller of a perfectly good, but indistinguishable, car is also trying to sell, but since he’s competing with you, he can’t get a price any higher than what you’re willing to accept for your “lemon.” The market starts to break down.

If sellers have so much more information about the product being sold than buyers do, how does anybody manage to get any business done at all? Dr. Akerlof wrote later, “Indeed, I soon saw that asymmetric information was potentially an issue in any market where the quality of goods would be difficult to see by anything other than casual inspection. Rather than being a handful of markets, the exception rather than the rule, that seemed to me to include most markets.”

If you don’t like the used car example, the job market for computer programmers is another tough one. How do you find someone who doesn’t just interview well and blitz through programming puzzles, but can actually add value to a complex project?

Anybody who buys or sells anything has to spend a lot of time getting around the asymmetric information problem.

And deceptive sellers learn new tricks too. Buyers and honest sellers get one thing figured out, and the deceptive sellers come up with something else. The CIO signing up for a site license faces the same problem as the tourist buying a “genuine Rolex” from a street vendor.

Why does any buyer trust any seller?

The prophet Jeremiah asked,

“Wherefore doth the way of the wicked prosper? Wherefore are all they happy that deal very treacherously?”

But the question we’re still trying to figure out is: wherefore do the honest prosper? Akerlof writes, “Dishonest dealings tend to drive honest dealings out of the market.” How can a market even exist? How can legit sellers earn anything?

Many institutions, norms, laws, and habits have popped up over thousands of years to deal with this problem.

Let’s require licenses for food vendors, and take away the license of anyone who sells tainted food.

Let’s only buy from sellers who offer a guarantee. Or let’s force all sellers to offer some kind of guarantee.

Let’s protect trademark rights for sellers, to give sellers a mechanism for building reputation and repeat business.

Advertising is another one.

Is advertising rational?

How can advertising help make it possible for honest buyers and sellers to work together?

Davis et. al. ask the question, “Is advertising rational?” and come up with:

“It is not so much the claims made by advertisers that are helpful, but the fact that they are willing to spend extravagant amounts of money on a product that is informative.”

That seems wasteful at first, but let’s work through the logic of it.

Buyers are ignorant about the quality of products from which they are choosing.

Buyers become better informed after buying and using a product.

Sellers have a good idea of product quality, and for what kinds of users the product is a good choice.

Sellers have an incentive to misrepresent products.

“What is needed, therefore, is some means of extracting truthful information from producers a means of distinguishing those producers who genuinely believe their product to be of high quality from those who do not.”

So what is a “screening mechanism” that will separate the sellers who believe their products to be of high quality from the deceptive sellers? The idea is to come up with some activity that is costly enough for low quality sellers that they won’t do it, but still affordable for high quality sellers.

Signaling

That’s where signaling comes in. In a market with asymmetric information, signaling is an action that sends a credible message to a potential counterparty.

Advertising spending is a form of signaling that shows that a seller has the money to advertise (which the seller presumably got from customers, or from investors who thought the product was worth investing in), and believes that the product will earn enough repeat sales to justify the ad spending.

Rory Sutherland, vice-chairman of Ogilvy Group, said,

To a good decision scientist, a consumer preference for buying advertised brands is perfectly rational. The manufacturer knows more about his product than you do, almost by definition. Therefore the expensive act of advertising his own product is a reliable sign of his own confidence in it. It is like a racehorse owner betting heavily on his own horse. Why would it be

rationalto disregard valuable information of that kind?

Richard E. Kihlstrom and Michael H. Riordan explained the signaling logic behind advertising in a 1984 paper.

When a firm signals by advertising, it demonstrates to consumers that its production costs and the demand for its product are such that advertising costs can be recovered. In order for advertising to be an effective signal, high-quality firms must be able to recover advertising costs while low-quality firms cannot.

Kevin Simler writes, in Ads Don’t Work that Way,

Knowing (or sensing) how much money a company has thrown down for an ad campaign helps consumers distinguish between big, stable companies and smaller, struggling ones, or between products with a lot of internal support (from their parent companies) and products without such support. And this, in turn, gives the consumer confidence that the product is likely to be around for a while and to be well-supported. This is critical for complex products like software, electronics, and cars, which require ongoing support and maintenance, as well as for anything that requires a big ecosystem (e.g. Xbox).

Evidence for the signaling model

Davis et al. conclude:

Advertising enhances the buying opportunities of consumers by alerting them to products about which they know little, and by signalling to them the seriousness of intent of the producer. It is more about informing them than acting as the persuasive door to door salesman. The salesman will persuade them to buy things they don’t need, but he won’t do that for very long.

In The Waste in Advertising Is the Part That Works, Tim Ambler and E. Ann Hollier describe a signaling test based on showing “expensive” and “degraded” versions of the same TV commercials to experimental subjects. The audience’s estimation of advertising expense had an effect on brand preferences.

[P]erceived expense rarely is an important direct predictor of brand choice. However, there is a very consistent, though largely indirect link between the two because perceived expense influences perceptions of brand quality, which in turn is the most critical predictor of a participant’s inclination to purchase a brand.

Ambler and Hollier split out the effects of familiarity, information, and persuasion from signaling. “[H]owever much attention, recall, and persuasion an advertisement may garner, the effectiveness of the advertisement, and thus brand performance, will depend on the perceived advertising expenditure.”

Philosopher Thomas Wells, in an essay for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, writes that advertising is a waste.

Like banks housed in grand marbled buildings, companies which pour vast amounts of money into advertising campaigns must be supremely confident about the quality of their products and its long-term sales. Otherwise they couldn’t afford to burn so much money on ridiculous Super Bowl ads. This argument rather reminds me of John Maynard Keynes’s suggestion that in a recession caused by a collapse of aggregate demand one could solve the problem by burying bottles filled with bank notes and then leaving it to private enterprise to dig them up again.

But signaling by advertising isn’t just based on the production values of the ad. Ambler and Hollier tested ads in isolation, but in the real world, ads appear attached to content. The signal is proportional to the value of the content, not just the ad itself. A comScore study found found 67% higher brand lift from ads that run on sites that are members of Digital Content Next, a trade organization for large, high-reputation online publishing companies. Expensive ad-supported resources such as journalism and cultural works are both a positive externality of advertising and a fundamental part of how advertising works.

How signaling breaks down

Advertising is one support member in the structure of a market. It bears some of the load of holding up the fragile tent under which honest people can do business with each other. Markets tend to fall apart because of information asymmetries, but advertising can help inform would-be buyers by revealing a seller’s beliefs about a product.

What happens, though, if sellers try to reduce the load that advertising carries, by “efficiently” targeting some users and not others?

The result is the peak advertising effect, where ad prices in a medium peak, then decline. From the user’s point of view, the more likely it is that the ad you’re seeing is custom-targeted to you, the less information the advertiser is able to convey. With good enough targeting, you could be the one poor loser who they’re trying to stick with the last obsolete unit in the warehouse. Targetable ad media tend to lose value as users figure out the targeting.

Advertising can break down as a signaling method when the medium gets noisy enough. Mark N. Hertzendorf explains, in “I’m not a high-quality firm, but I play one on TV” (RAND Journal of Economics, vol. 24, number 2, summer 1991.) On the subject of the signaling model: This result, however, is sensitive to the assumption that consumers can perfectly observe the firm’s advertising expenditure. This assumption is somewhat unreasonable in light of the fact that much advertising takes place over various electronic media to which not everyone is ‘tuned in.’

Hertzendorf writes, Furthermore, the noise complicates the process of customer inference. This enables a low-quality firm to take advantage of consumer ignorance by partially mimicking the strategy of the high-quality firm.

That’s in an environment where the presence of many TV channels makes it harder for the audience to figure out who’s really trying to signal. Noise helps deceptive sellers. The result is that high-quality sellers lose some rewards of advertising, because they become harder to distinguish from low-quality sellers.

Where low-quality sellers in Hertzendorf’s scenario must rely on increasing noise in the medium in order to deceive, targeting creates opportunities for deceptive sellers to make the first move. Pedro M. Gardete and Yakov Bart describe a game in which message senders try to persuade message receivers to respond, and can modify their messages based on knowledge of each receiver’s location.

When the messaging system allows senders to tell receivers what they want to hear, then receivers choose to ignore messages. In order to keep their messages credible, senders must limit their knowledge about receivers. Gardete and Bart write, We find that the sender prefers not to learn the receiver’s preferences with certainty, but to remain in a state of partial willful ignorance. The receiver prefers complete privacy except when information is necessary to induce communication from the sender.

Advertisers who choose targeting are usually not deliberately deceptive. However, a medium that facilitates targeting also facilitates deceptive communication. When developers choose to make a communications medium more targetable, they reduce the maximum amount of information that advertising in that medium can provide to its audience, drive down the value of advertising in the medium, and give the audience an incentive to block.

But what happens if targeting actually starts working?

For targeted advertising, it’s damned if you do, damned if you don’t. If it fails, it’s a waste of time. If it works, it’s worse, a violation of the Internet/brain barrier. The Facebook emotion experiment is making the second possibility more realistic.

Betsy Haibel writes, in The Fantasy and Abuse of the Manipulable User,

“Banner blindness” - the phenomenon in which users become subtly accustomed to the visual noise of web ads, and begin to tune them out - is a semiconscious filtering mechanism which reduces but does not eliminate the cognitive load of sorting signal from noise. Deceptive linking practices are intended to combat banner-blindness and increase exposures to advertising material. In doing so, they sharply increase the cognitive effort required to navigate and extract information from websites.

If it’s just one brain versus the collective manipulation power of the entire Internet industry, we’re doomed. But our species has been fighting off temptations for a long time. Users have those mental filters, but in the long run tend to build and use other tools. Haibel again:

“Growth hacking”—traditional marketing’s aggressive, automated, and masculinely-coded baby brother—will continue to expand as a field and will continue to be cavalier-at-best with user boundaries.

Boundary-testing is not news. The boundary between self and not-self has been under attack for thousands of years, by ancient and terrible enemies such as addiction and political extremism. If users can beat those, and a certain number must be able to in order to carry on the species, they will be able to apply the same defenses to marketing. Users have four lines of defense:

Willpower

Habit power

Technology

Regulation

Listed from fastest-acting, most responsive, to slowest-acting, least responsive. When one proves too tiring or costly, users fall back on the next one. Targeted advertising is unlikely to extinguish the decision-making self, but what looks like its promise from the marketing side looks like risk from the point of view of a mindful buyer. High-profile successes tend to inspire users to defend themselves.

Awareness of targeting is still growing

If an individual is aware that targeting is possible but doesn’t know if each individual ad in a medium is targeted, the signal, even that carried by non-targeted ads, is lost. As users learn about targeting, the value of the entire medium is going down, even for advertisers who do not target.

However, some buyers are still unaware of the extent of targeting. One politician saw an ad for a dating site on a political party press release and attributed it to the party, not to the Google ad service used on the site where he read it. From inside the IT business, a lot of tracking and targeting schemes look old and obvious, but some of the audience is still figuring it out.

And the faster they figure it out, the faster the value of targeted ads is going away.

Targeting failure

All of this isn’t just hypothetical—it has happened before. We can get some hints about the future of targeted web advertising from the history of email spam. Remember CAN-SPAM? This was the US Federal law that overruled state spam laws, some of which were strict, and cleared the way for advertisers to send all the spam they wanted, as long as they followed a few basic rules. Spam fighters had an effective tool in the form of state “private right of action” laws, but CAN-SPAM took them away. The law was a huge victory for pro-spam lobbyists at the Direct Marketing Association.

Today, the data, the tools, and even the law are all there for advertisers to take full advantage of email spam. The CAN-SPAM debate is over. The Internet privacy nerds lost, and database marketing won.

So where is all the CAN-SPAM-compliant spam?

Web ads promise targeting, but spam has been able to deliver it for a long time. Why aren’t advertisers using it?

User targeting promises a way to reach users without paying for expensive content. In Ad Age, Adam Lehman, COO and General Manager at Lotame, writes, With the enormous variety of information available through the Internet, I am able to do research on running shoes across diverse sources. Based on the interests I express through my research, I may be presented with downstream advertising offers, which I can take or leave.

The key word here is “downstream.” Lehman goes to a running site and somehow expresses interest in shoes. Later, while he’s browsing some other, possibly unrelated, site, an advertiser “retargets” him with a shoe ad. The “downstream” site can be running whatever is the cheapest content that Lehman is willing to look at at all. Instead of having to place ads on relevant content, an advertiser can chase the user onto cheaper and cheaper sites.

What if you took everything that web ad targeting promises, and actually delivered it? Deliver ads to the exact right user? Sure. Go by email addresses which are in marketing databases already. Save money on content? Try free. Take every ad targeting concept and max it out, and you get email spam.

But what’s wrong with that? John Battelle writes,

It’s actually a good thing that we as consumers are waking up to the fact that marketers know a lot about us—because we also know a lot about ourselves, and about what we want. Only when we can exchange value for value will advertising move to a new level, and begin to drive commercial experiences that begin to feel right. That will take an informed public that isn’t “creeped out” or dismissive of marketing, but rather engaged and expectant—soon, we will demand that marketers pay for our attention and our data—by providing us better deals, better experiences, and better service. This can only be done via a marketing ecosystem that leverages data, algorithms, and insight at scale.

As they say on the Internet, dØØd wtf? The first step in me getting a better deal is for the other side to have more information about me, and for me to be engaged and expectant

about that? In the real world, people make the rational decision to supply fake data instead.

A cold call is not advertising

Email spam is the digital version of direct mail, which is the paper version of a cold call. The problem with all this targeted communication is that it’s based on extremely fine-grained data on the seller’s side, and none on the buyer’s.

An advertisement that’s tied to content, in a clearly expensive way, sends a signal from the advertiser to the buyer. The extreme example here is an ad in a glossy magazine. It’ll still be on that magazine years later, and every subscriber gets the same one. Almost ideal from a signaling point of view. The other extreme is a cold call, which carries no “proof of work” or signaling value. All the information is on the seller’s side, so the cold call is of no value to the recipient.

Which is why users block email spam. It’s worthless. Even spam that complies with CAN-SPAM is worthless. And web ads are steadily moving further and further away from magazine-style, with signaling value, toward spam-style, with no signaling value.

Targeting failure: legit sites lose, intermediaries win

Ricardo Bilton asks, While behavioral advertising may be vital to the current makeup of the web, the question worth answering now is this: Is that really the kind of Internet that we want to use in the first place?

Good question. Alexis C. Madrigal writes, The ad market, on which we all depend, started going haywire. Advertisers didn’t have to buy The Atlantic. They could buy ads on networks that had dropped a cookie on people visiting The Atlantic. They could snatch our audience right out from underneath us.

And Michael Tiffany, CEO of advertising security firm White Ops, said, The fundamental value proposition of these ad tech companies who are de-anonymizing the Internet is,

Why spend big CPMs on branded sites when I can get them on no-name sites?

Walt Mossberg recounts a dinner conversation with an advertiser:

NBC, which was one of our investors, had a dinner and we each stood up and said a few words. But we were seated next to the head of this advertising company, who said to me something like,

Well, I really always liked AllThingsD and in your first week I think Recode’s produced some really interesting stuff.And I said,Great, so you’re going to advertise there, right? Or place ads there.And he said,Well, let me just tell you the truth. We’re going to place ads there for a little bit, we’re going to drop cookies, we’re going to figure out who your readers are, we’re going to find out what other websites they go to that are way cheaper than your website and then we’re gonna pull our ads from your website and move them there.

Publishers call the problem data leakage, and it drives a race to the bottom for ad revenue on news and other original content sites.

Doug Weaver writes, One can argue, and maybe I’m the first one to do it, that all this targeting and audience segmentation might be creating an internet that’s worse for the consumer. By downplaying the need for context, we’re actually dis-incentivizing the creation of quality content and environments.

According to AOL CEO Tim Armstrong, only 25% - 45% of online ad spending makes it as far as the publisher. Nanigans CEO Ric Calvillo says, “The typical markup on media is 100 percent,” at the ad exchange layer. A Technology Business Research survey found 40% of digital advertising budgets going to “working media”.

When advertisers decide to chase users from site to site in search of lower rates, where do the ads end up? In a lot of cases, on illegal sites. Chris Castle points out that McDonald’s ads are running on sites that carry infringing song lyrics.

Another example is BMW’s Response to Ads for Its Brands on Pirate Sites. Somehow, BMW advertising ended up running on an illegal album download page, on a site called mp3crank. Ad networks do respond to pressure from copyright holders and remove ads from known infringing sites, but snatching revenue from original content sites is still a major effect of tracking.

How targeted ads fail brand advertisers

Brand advertisers, who Doc Searls splits out from direct response advertisers, are looking for alternatives. John Hegarty, founder of the ad agency Bartle Bogle Hegarty, said, I’m not sure I want people to know who I am. I find that slightly Orwellian and I object to it. I don’t want people to know what I drink in the morning and what I drink at night. I think there’s a great problem here - throughout history we have fought for our freedom to be an individual, and you’re taking it away from us. I think there’ll be a huge backlash to that and Nike will have to be very careful.

And Richard Stacy writes, The great thing about advertising is that no-one takes it personally.

Rory Sutherland of Ogilvy Group also comments,

A very intelligent British adman makes the distinction between ads which create sales and ads which create saleability. The kind of adspend-as-signalling Don refers to is very much about creating saleability rather than sales. Conventional media do a better job of this signalling, which may be complementary to—and not replaceable by—money spent online.

Am I right? Testable predictions

Print advertising will keep its premium in spending per user minute. The harder it is to do targeting in a medium, the more valuable the medium is. (Right so far)

Higher awareness of the extent to which online ads are customized to the user will be correlated with higher use of tracking protection. (Users want to see “who’s advertising on example.com”, not ads with “relevance”.)

The more tracking protection that a user has, the more money he or she spends online, even when controlling for demographics, time spent online, and Internet skill. (Avoiding information asymmetry is an important motivation for using tracking protection.) (Right so far: Before being acquired by Yahoo, ClarityRay published a survey showing that users of ad blockers spend more money online.)

In jurisdictions where user tracking is limited by law or regulation, web publishers will earn more revenue per user, as projected in a paper by Henk Kox, Bas Straathof, and Gijsbert Zwart.

Some product and service categories (cars, insurance) are still rarely sold online. Tracking-protected users will be over-represented in the early adopter group who are buying these categories online, even when controlling for demographics, time spent online, and Internet skill. Signaling matters more than matching.

What next? Solutions

Solution: tracking protection

The best thing that you, as a user, can do to get better ad-supported content is to install a tracking protection tool. Why?

It’s possible for both of these to be true:

This individual ad will have a higher click-through rate if we personalize it to the user.

and

Online advertising as a whole will be less profitable if we personalize ads to users.

Advertisers and legit content sites would do better if nobody tracked users, but if some advertisers track and others don’t, the ones who do can have an advantage. As long as users believe that online advertisers target ads, any non-targeters won’t get the credibility benefit they deserve.

Statistics about performance of individual ads feed into dangerous self-deception about the industry-wide effects of targeting. However, as the audience begins to understand targeting, the rate of ad blocking increases, the value of web ads decreases, and increasingly crappy ads drive more user demand for ad blocking.

Fortunately, easy-to-use tracking protection makes targeting more difficult and less accurate. Tracking protection makes the value of advertising across the entire medium rise, it’s harder for ad networks to get leaked audience data from high-reputation sites, and those sites will be able to get more ad revenue and control, at the expense of middlemen.

Just as targeting didn’t have to work with total accuracy to give an advantage to deceptive signalers, tracking protection doesn’t have to be 100% to push things back in the other direction.

Solution: flight to quality

Henk Kox, Bas Straathof, and Gijsbert Zwart, in Targeted advertising, platform competition and privacy, write,

We find that more targeting increases competition and reduces the websites’ profits, but yet in equilibrium websites choose maximum targeting as they cannot credibly commit to low targeting. [emphasis added] A privacy protection policy can be beneficial for both consumers and websites.

The way that the gamesmanship of tracking works out, high-value content sites end up participating in ad targeting systems that are against their interests.

If websites could coordinate on targeting, proposition 1 suggests that they might want to agree to keep targeting to a minimum. However, we next show that individually, websites win by increasing the accuracy of targeting over that of their competitors, so that in the non-cooperative equilibrium, maximal targeting results.

The missing piece is that on the real web, users can switch browsers or install tracking protection tools to adjust the level at which they are targeted. The right set of tracking protection tools can increase revenue for publishers.

And publishers have more options than just “target more” or “target less”. For example, another move that’s available to a site is to encourage the use of tracking protection. Publishers could identify tracking-protected users and offer them some kind of bonus content, such as single-page views of long paginated articles, full interview transcripts, or a forum for submitting questions to ask in upcoming interviews. Site functionality that makes certain content available only to untracked users is sometimes called a “reverse tracking wall.”

A good real-world example is the “car intender” problem. Today, when an intermediary can target a specific user based on that user’s interest in car reviews, the value of a some ad impressions served to that user on unrelated sites is artificially increased. Tracking means that the car review site fails to capture some of the value of its own content. When the car review site encourages the user to use tracking protection, by placing bonus photo galleries behind a reverse tracking wall, some “car intender” impressions on unrelated sites disappear from the market.

For a publisher, a reverse tracking wall reduces the amount of data collected and can reduce the saleability of some ad inventory in the short term. High-reputation sites, however, can benefit in the long run by denying data to intermediaries and low-reputation sites. And it’s not a zero-sum game. Impressions served to tracking-protected users have signaling value that targeted ones lack.

Solution: tracking protection for publishers

Nudging the returns on tracking down by promoting tracking protection is one way to give advertisers an incentive to spend more on supporting content and less on targeting users. However, classifying users into vulnerable and protected requires sites to use a separate domain for testing. Original content sites are likely to need a third-party service to detect trackability by third-party services.

Because “malvertising,” or malware distributed through ad networks, is a growing problem, some kind of third-party content filtration is going to join the basic recommended list of security software for regular users, along with firewall and antivirus. The question is whether the anti-malvertising slot on the shopping list will be filled with a problematic and coarse-grained ad blocker, or with a publisher-friendly tracking protection tool such as Disconnect or the built-in tracking protection in Firefox.

Sites can influence, not just observe. Instead of waiting for more and more users to grab the default ad blocker, sites can help and encourage users to run better tracking protection tools. The more that sites fail to pay attention, or dismiss all tracking-related security concerns, the more users are likely to switch to a “dumb” ad blocker, and the more that web ads could slide into a no-win struggle like email spam/anti-spam. Examples of constructive first steps are to replace confusing tracking opt-outs with links to a tracking test, and to recommended tracking protection measures chosen for the user’s browser.

This solution is implemented here: Tracking Protection for Publishers.

Solution: give brand advertising a seat at the table

The current policy debate on web tracking is going much the same way that the debate on email spam did. Responsible users of email for marketing abandoned the debate and let the lobbyists at the DMA get CAN-SPAM passed in 2003. That only helped the bottom-feeders of marketing (who probably don’t pay for DMA memberships anyway) and started a frustrating, expensive struggle for real DMA members to get their legit email newsletters delivered to users.

The DMA focused on spammers and failed its mainstream, non-spammer membership in 2003. The IAB is focusing on intermediaries and failing mainstream advertisers and publishers today. There are a lot of details to work out about how the norms and protocols for online ads have to change to support brand advertising, and not just direct response.

Brand advertisers need to send a credible signal, and tracking protection for users helps reinforce that signal. The less targetable that web advertising is, the more valuable that brand advertisers will find it. We will probably need a post-IAB organization for higher-value online advertising, and leave IAB to concentrate on tracking and direct response.

Solution: respect

Peter Klein of MediaWhiz, writing in Ad Age, explains Why Do Not Track Will Make Online Advertising Better (Seriously).

Anti-tracking legislation will make online advertising more focused and relevant to consumers. It will set into motion a more innovative and prosperous era of digital marketing, dominated by a healthy respect for consumers’ wishes about how their data are collected and used, and innovative advertising that meets their needs.

Making tracking harder is just what advertising needs. Klein writes,

Do Not Track will force marketers to be more creative in their campaigns, tapping into legally available data—users’ expressed interests. This will foster deeper and more relevant connections between brands and consumers and benefit online advertisers in the long run.

Tracking protection isn’t just good for advertising, it’s good for the content creators. All but the least reputable content sites are likely to do better on a web where users are less targetable. While Europe pursues regulation, tracking protection in the USA is likely to come from client-side software improvements, not from the government.

Conclusion: don’t panic

I once worked on a web site for a client who showed me another marketing project at the company. It was an animated Christmas card, delivered by email. The file type of the attachment: Microsoft Windows .EXE. Naturally, I pointed out that (1) In those days, when Windows 95 and 98 were the most common client platforms, the .EXE can basically do anything—read the user’s files, trash other programs, whatever. And (2) Internet email is forgeable. The “From:” address can be totally fake. So who’s going to open a .EXE that comes in via email?

Naturally, I was wrong. “Given a choice between dancing pigs and security, users will pick dancing pigs every time.” The customers loved the Christmas card.

Today, though, we have different norms and technologies around security. A .EXE in email will get quarantined, filtered, or buried under layers of warnings.

The same thing is happening with ad targeting problems. Browser developers are steadily closing the bugs that make tracking possible. And yes, that makes some advertising techniques obsolete, the same way that corporate virus checkers killed off the animated .EXE Christmas card business.

But if you want to send customers a holiday greeting, you still can. And after the web fixes its tracking bugs, you’ll still be able to advertise. It will just work better.

Easy first steps

Is your browser safe from third-party tracking? Help your favorite sites by taking a quick test and getting protected if you need it.

To protect your web site’s users from fraud and malware, while increasing the value of your brand and your content, you can add one line of JavaScript from Aloodo to your site.

If your site shows a message for users running ad blockers, make sure to detect and handle tracking protection. Tracking protection tools work in the interest of high-quality sites, while ad blocker practices such as paid whitelisting work in the other direction. This page has a warning for ad blocker users without tracking protection. (try it).

Discuss

Changelog

June 2017: Add Internet Trends 2017 data.

August 2016: Add comScore study.

June 2016: Add Mossberg quotation. Add Nielsen link.

May 2016: Add Gardete and Bart summary. Add Internet Trends 2016 data.

May 2015: Add Internet Trends 2015 data.

March 2015: Expand Ambler and Hollier info. Cut some Davis material. Add material on Apple and reverse tracking wall model.

February 2015: Break out signaling section. Replace confusing instances of the word “privacy”. Add “tracking protection for publishers” section. More rewrites.

December 2014: Rework Internet Trends section, add chart.

September 2014: Kevin Simler quotation and link.

July 2014: Mention private right of action in CAN-SPAM section, rework brand advertising solution section. Add Doug Weaver quotation and link. Add flight to quality section. Mention Haibel article. Move Turow link and discussion up. Add Calvillo quotation.

June 2014: Add link to Turow et al. survey. Add 2014 numbers from Mary Meeker presentation.

October 2013: Add Michael Tiffany quotation. Add Slashdot and Doc Searls Weblog links. Remove a duplicated quotation. Add link to Ambler and Hollier paper.

September 2013: Break out It’s not about the data, add a link.

July 2013: Original version.